The Body Wants to Live (2020)

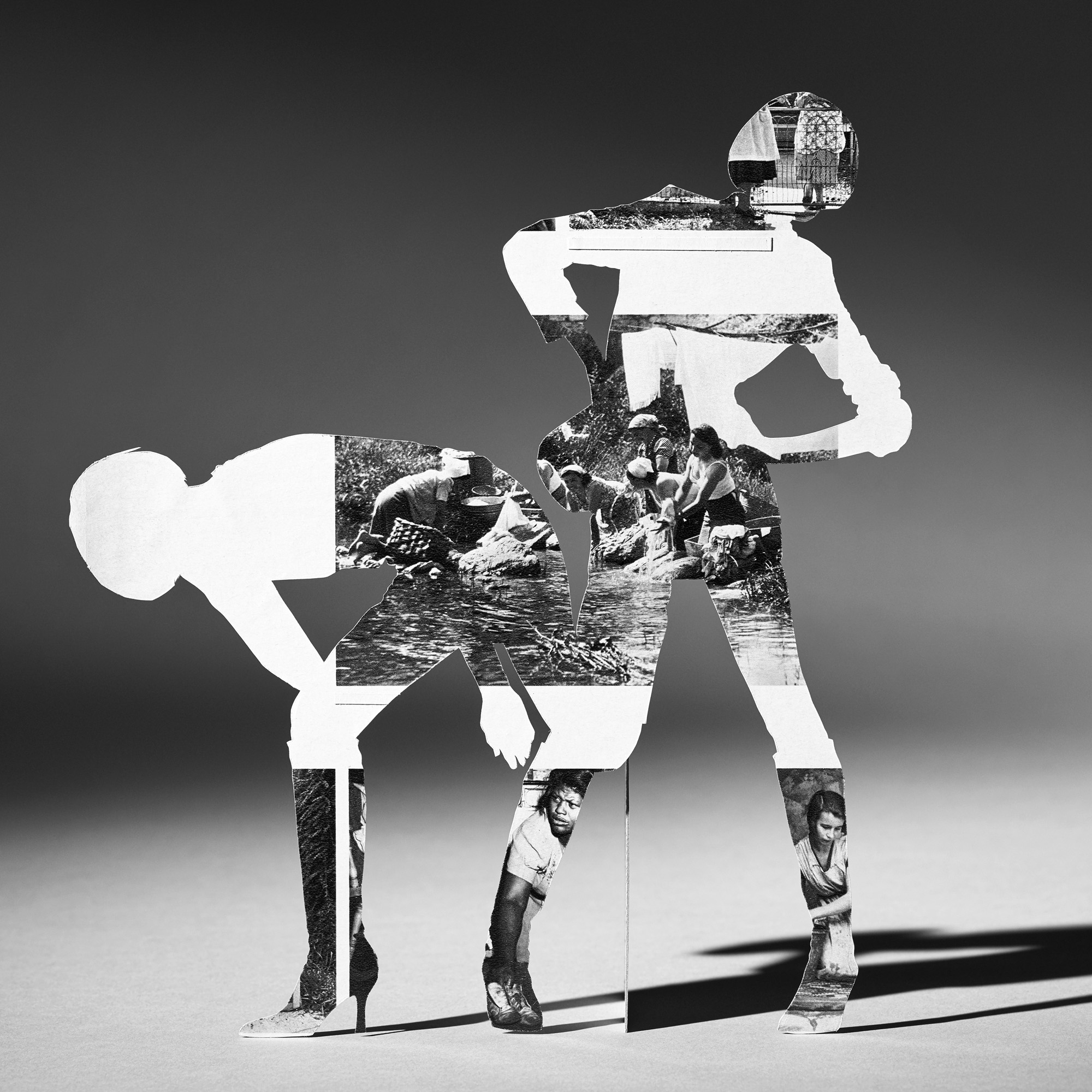

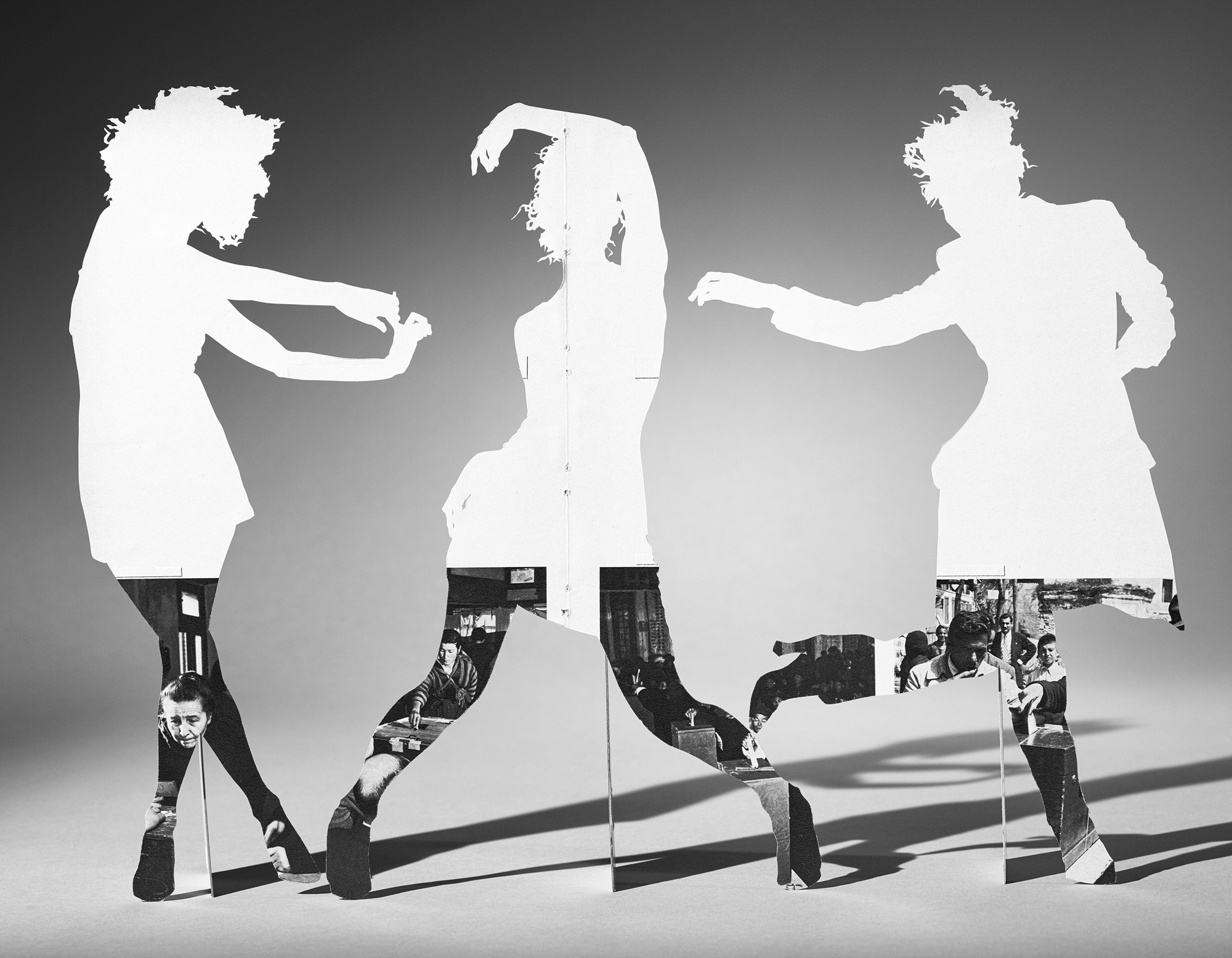

The Body Wants to Live sources iconic silhouettes from Richard Avedon’s 1990s campaign for Gianni Versace to frame and reanimate the pages of The Family of Man catalogue that accompanied the eponymous 1955 MoMA exhibition curated by Edward Steichen. Echoing the original exhibition’s layout, the catalogue is filled with small, boxed images that propose a universal narrative from creation to death arranged on white pages. Lipps explores the contrast between the high fashion sensibility of Avedon’s silhouettes and the reconfigured content of their interior photographs, highlighting the wealth and racial disparities that have been in especially sharp focus today. Lipps transforms this printed publication into theatrical tableaux employing collage strategies, sculptural devices, and dramatic staging. Studio lighting combines portrait and product photographic techniques to illuminate the dynamically posed bodies, lending a film noir aura to the surreal fashion photoshoot.

The Body Wants to Live sources iconic silhouettes from Richard Avedon’s 1990s campaign for Gianni Versace to frame and reanimate the pages of The Family of Man catalogue that accompanied the eponymous 1955 MoMA exhibition curated by Edward Steichen. Echoing the original exhibition’s layout, the catalogue is filled with small, boxed images that propose a universal narrative from creation to death arranged on white pages. Lipps explores the contrast between the high fashion sensibility of Avedon’s silhouettes and the reconfigured content of their interior photographs, highlighting the wealth and racial disparities that have been in especially sharp focus today. Lipps transforms this printed publication into theatrical tableaux employing collage strategies, sculptural devices, and dramatic staging. Studio lighting combines portrait and product photographic techniques to illuminate the dynamically posed bodies, lending a film noir aura to the surreal fashion photoshoot.

Fashion photography has long been an inspiration to Lipps’s practice. Having come of age in the 90’s, he cites an early preoccupation with mass-distributed fashion magazines as both a creative and personal awakening:

“Worshipping those pictures as a closeted, queer kid, I fell in love with photography and found a safe relation to the world (at a distance). While fashion images privilege style over substance, you cannot dismiss the substance at play and how highly manipulated and manipulative all photographs are. I learned at a tender age to police my own and others’ genders; I grew disdain for how I saw and held my body; I adopted unhealthy attitudes about wealth and whiteness; and, I bought all of it! This purchase is the stealth and seduction of photography. A photograph of war and a photograph of a model are both photographs. As photography grows exponentially more sophisticated than the lexicon used to prop up our understanding of its operation, we are perpetually reconfiguring ourselves and our relationships in attempt to operate it.”

“Worshipping those pictures as a closeted, queer kid, I fell in love with photography and found a safe relation to the world (at a distance). While fashion images privilege style over substance, you cannot dismiss the substance at play and how highly manipulated and manipulative all photographs are. I learned at a tender age to police my own and others’ genders; I grew disdain for how I saw and held my body; I adopted unhealthy attitudes about wealth and whiteness; and, I bought all of it! This purchase is the stealth and seduction of photography. A photograph of war and a photograph of a model are both photographs. As photography grows exponentially more sophisticated than the lexicon used to prop up our understanding of its operation, we are perpetually reconfiguring ourselves and our relationships in attempt to operate it.”

In Steichen’s words, photography was uniquely suited for “giving form to ideas” and “explaining man to man”. The Family of Man exhibition aimed to function “as a mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world.” The United States Information Agency (1953-1999) produced 5 versions of the exhibition that would tour the world for 8 years and was seen by over 9 million people, while the enduring publication has sold over 4 million copies and has never been out of print. While deserving of accolades for its innovative design and ambitious curatorial premise, it was also met with heavy criticism for papering over problems of race and class and for presenting a United States-centric view of the world and non-Western cultures. According to Lipps, “The USIA was a propaganda machine. It saw an opportunity in this exhibition to masquerade behind a sentimental humanist message in order to smuggle colonizing directives encoded in photographs to promote global domination of distinctly ‘American values’—patriarchy, white supremacy, heteronormativity, and religiosity propagated by capitalism.” As, Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography "By purporting to show that individuals are born, work, laugh, and die everywhere in the same way, The Family of Man denies the determining weight of history - of genuine and historically embedded differences, injustices, and conflicts.”

In an essay accompanying the exhibition, William J. Simmons writes:

“Criticality is itself a shroud of sorts that reduces the photograph to another binary condition of being either deconstructive or complicit. We cannot say of Lipps’s work that, as is often remarked of Martha Rosler’s political photomontages, the spectral images of the “real” world haunt the pristine, glossy pages of Better Homes and Gardens and Vogue and the never-out-of-print exhibition catalogue for “The Family of Man,” as if we need the pasticheur to tell us that war reportage and Versace and Avedon and porn and racist curatorial strategies exist on the same plane. We know this because we live in that coextensive state, and, as with Rosler and Barbara Kruger, for that matter, the power of Lipps’s work lies not in the easy condemnation of a juxtaposition, but rather in the uncomfortable and erotic space of repulsion and guilt admixed with love.”

To read the full text by Simmons, please click here.

“Criticality is itself a shroud of sorts that reduces the photograph to another binary condition of being either deconstructive or complicit. We cannot say of Lipps’s work that, as is often remarked of Martha Rosler’s political photomontages, the spectral images of the “real” world haunt the pristine, glossy pages of Better Homes and Gardens and Vogue and the never-out-of-print exhibition catalogue for “The Family of Man,” as if we need the pasticheur to tell us that war reportage and Versace and Avedon and porn and racist curatorial strategies exist on the same plane. We know this because we live in that coextensive state, and, as with Rosler and Barbara Kruger, for that matter, the power of Lipps’s work lies not in the easy condemnation of a juxtaposition, but rather in the uncomfortable and erotic space of repulsion and guilt admixed with love.”

To read the full text by Simmons, please click here.

For inquiries about exhibitions and sales:

LOS ANGELES

Marc Selwyn Fine Art

9953 South Santa Monica Blvd.

Los Angeles CA 90212

info@marcselwynfineart.com

NEW YORK

Yancey Richardson Gallery

525 West 22nd Street

New York, NY 10011

info@yanceyrichardson.com

LONDON

Josh Lilley Gallery

44-46 Riding House Street

London W1W 7EX

info@joshlilley.com

For other things:

Email: Matt Lipps

Instagram: @_mattlipps_